Is The Cryptocurrency Craze Just History Repeating Itself?

Bitcoin has been seeing more than its fair share of headlines in recent months, but is the craze justified, or being fuelled by questionable speculation?

In December 2017, the value of the crypto asset surged to almost $20,000 per coin. While its price fell sharply in the following months, the value of one Bitcoin currently stands at $39,303 or £28,171 (as of 19 June 2021).

The world has yet to discover if this is a bubble waiting to burst.

As we wait, now is an ideal opportunity to look back in the annals of time for some historical parallels…

Tulip fever – Holland (1634-1637)

Tulips were introduced to the Netherlands from Turkey in 1593.

By the time tulip fever took hold, the Dutch Republic had some of the most advanced financial institutions in Europe, including the first official stock exchange, capital market and central bank.

The new and sophisticated financial system encouraged people to invest and trade in ways that had never been seen before. And one result of the new innovations was the introduction of trading futures.

When merchants began trading futures of tulip bulbs, which were already a luxury commodity at the time, it wasn’t long before a bubble began to form.

Everyone began to deal in bulbs. People were essentially speculating on the tulip market, which they believed would continue to grow without limit.

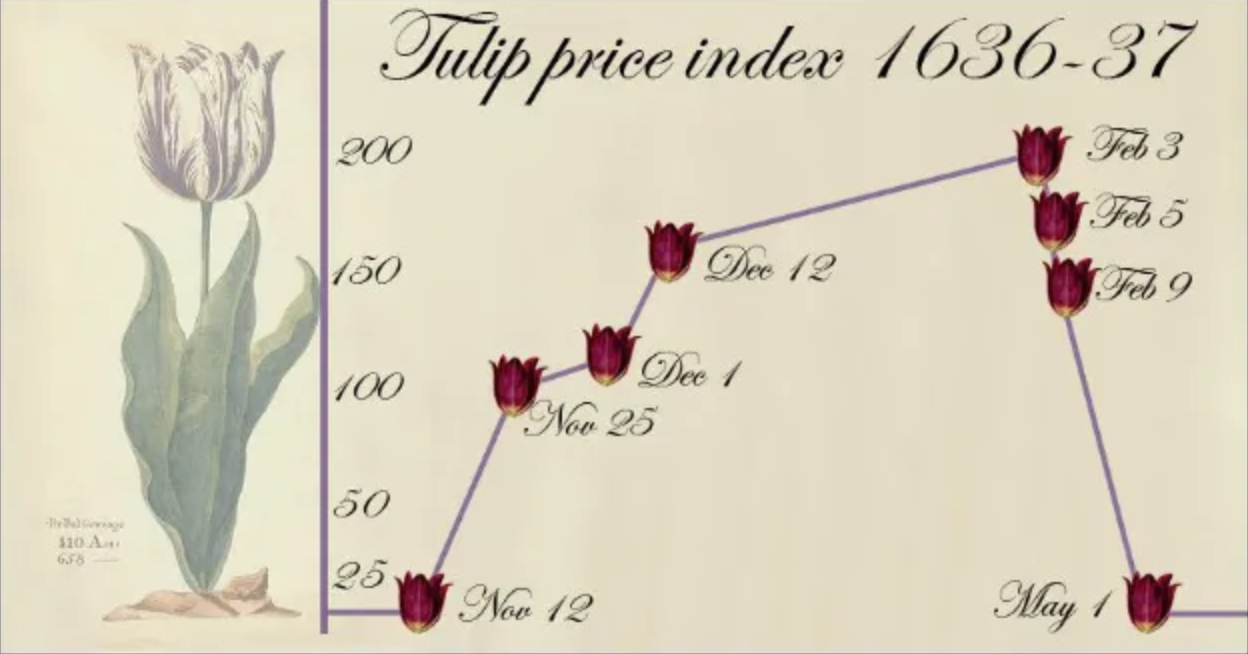

The numbers

At the height of the frenzy, futures contracts for tulips were exchanged as many as 10 times per day, driving their price up, often to several dozen times their true value.

The most expensive tulips cost around 5,000 guilders (enough to buy a good house). The price of traded tulips rose 59-fold over around 16 months, before collapsing back to almost zero a few months later.

Source: Sukant Khurana

When the bubble burst, the price of a tulip bulb collapsed overnight. Those who had sold their homes for a slice of the action suddenly found themselves empty-handed.

Tulip fever is a great example of commodity speculation getting out of hand, but bad business speculation can also be problematic for financial markets.

Railway mania – United Kingdom (1862)

Once the go-to investment for affluent Victorians, interest rates in mid-19th century Britain made gilts suddenly far less attractive.

Industrialisation had created a strong middle class with capital to invest and enough financial knowledge to make informed decisions about what was best for their money.

In 1830, the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was a huge commercial success, resulting in a flurry of applications for additional lines to be built:

- In 1843 Parliament received 63 applications

- By 1844 there were 199

- By the end of 1845, there were 562.

Buoyed by the success of the Liverpool to Manchester line, many middle-class investors were attracted by the investment opportunity. But as smaller lines proved less commercially viable, consumer confidence evaporated, stock prices fell, and many investors were left penniless.

Although bad news for many investors, by 1850, Britain had 6,000 miles of working railway lines.

The dotcom bubble – USA (1995-2001)

In the mid-nineties, the internet increased in popularity and triggered a wave of speculation in “new economy” businesses. These new start-ups needed funding, which initially came from venture capital firms.

Instead of being grounded on fundamental company analysis around revenue potential, business plans, industry analysis and market trends of Price Earnings ratio (P/E), many investors targeted their sights purely on the growth of traffic to the website.

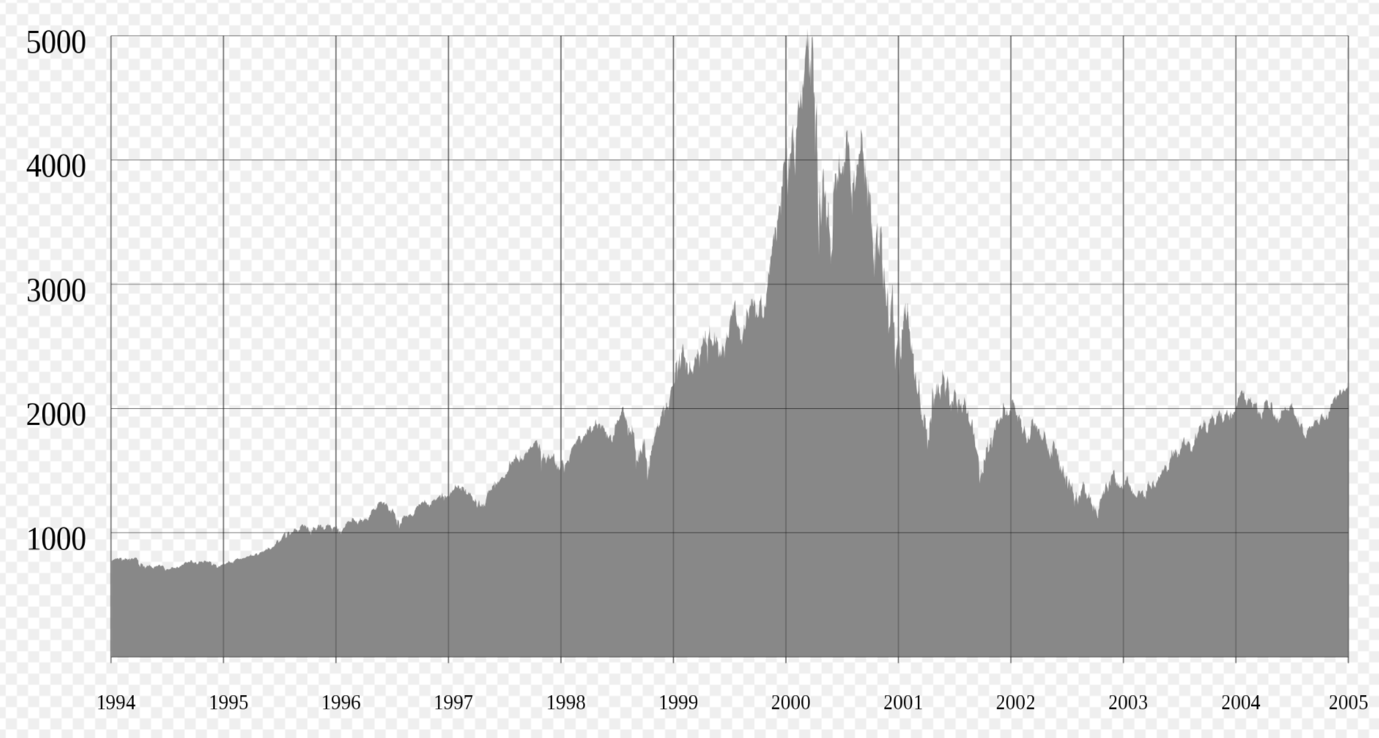

Based on these questionable business models, hundreds of dotcom companies went public and achieved immediate multimillion valuations. As a result, the NASDAQ, home to many of these technology company stocks, soared from a level of just below 500, at the start of 1990, to peak at over 5,000 in March 2000.

Shortly after, the index crashed. It dropped almost 80% over 18 months and triggered a US recession.

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/a790c796-f0c4-4cf9-8c7a-3b52daff89e4

It took more than 15 years to reach a new high in 2015.

Causes of the dotcom crash

A look at the primary causes of the dotcom bubble mirrors what we have seen in recent months with Bitcoin.

The three main factors that are attributed to the dotcom crash are:

- Overvaluation – focus was on website traffic metrics without value addition, resulting in unrealistic valuations driven by demand for the next investment opportunity.

- Abundance of venture capital – venture capitalists and other investors were pouring money into funding tech and internet company start-ups. This, coupled with low barriers to entry, led to massive investment in the sector, further fuelling the bubble.

- Media frenzy – News media outlets encouraged people to invest in tech stocks by promoting overly optimistic expectations on future returns. The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Bloomberg, and many other investment analysis publications all spurred demand and further inflated the bubble.

Some may argue it’s too soon to say whether cryptocurrency is another bubble, but history shows it would be prudent to be cautious if entering the game at this stage.

As with any investment, do your research to ensure the opportunity is real and, crucially, don’t invest more than you can afford to lose.

Get in touch

If you would like to discuss how we can help you invest your money for long-term, please get in touch. Email us at hello@firstwealth.co.uk or call 020 7467 2700.

This document is marketing material for a retail audience and does not constitute advice or recommendations. Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amount originally invested.

Let's Talk

Book a FREE 30-minute Teams call and we’ll answer your questions. No strings attached.

Check Availability